Report on the

Virgin

and Child with the Infant St

John the Baptist, Moscow, private collection

Thereza

Wells

July 2016

Aims

The aim of this paper is to investigate the Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist (private collection, Moscow) and how it might be placed within the artistic outputs of Leonardo da Vinci, his studio and his followers. It will assess the imaging campaign undertaken

with Art Analysis and Research Ltd. during the period October 2015 – March 2016 during which 4 paintings related to the Moscow picture

were examined using infrared imaging technology. The material obtained from the imaging campaign has been greatly informative in

understanding how the group of paintings might relate to the Moscow painting, to each other and to a wider group of paintings in and around

the Leonardo circle.

This paper will first briefly introduce the key paintings that formed our study and those that were part of the imaging campaign. It will then investigate the compositional, stylistic and iconographical elements of the Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist, as well as

how and why it might have been produced. This will be followed by a close look at the material obtained during the imaging campaign in order

to further understand how the paintings relate to each other and how they inform us about the practices of Leonardo, his studio and his followers. It will consider who could have produced the works in the core group and why and it will suggest where the Moscow work might be

placed within the context of these pictures and the artists who created them.

The Research Campaign

Paintings should never be studied in isolation. To be understood a painting must be viewed within the context of an artist’s oeuvre or influence, the period in which it was made, the artists who influenced it’s maker, etc. This is particularly true when a work has been replicated during a

contemporary or close to contemporary period. Why would a painting be replicated and how does one painting stand within such a group of

paintings? This is the case with the Moscow painting. The project was extremely fortunate to be given the opportunity to study the key works connected to the Moscow example. This had never been done before and it was an essential step in helping to more fully understand the work.

The Moscow painting forms part of a group of four works which share the same composition and they are

referred to as the ‘core’ group. There is a fifth work with the same composition but it is not included in the

‘core’ group

.

2 because of its apparent poor quality and unknown location (fig.1). Another three pictures in tondo

form are less like the ‘core’ composition but are close to each other. One of these tondos was included in the

imaging campaign.

The location of one tondo is unknown and the third, not studied, is in Milan. A further painting in Budapest

stands alone in many ways, but as will be found, is fundamental to our understanding of the Moscow

composition. These eight paintings form what is termed the ‘Moscow group’. Of the eight pictures, the

Florence, Oxford, Budapest and Buscot works comprised the imaging campaign.

Figure 1. Franciabigio, Madonna and child with st. John

The ‘Core’ Group

Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist (not imaged) Oil, tempera and gold on poplar.

71.8 x 50.5cm

Private Collection, Moscow

Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist

Attributed to Fernando Llanos or Fernando Yanez de la Almedina

Oil on panel

73 x 50cm

Galeria Palatina, Florence

Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist Circle of Leonardo da Vinci

Oil on panel, possibly linden.

72.2 x 50.5cm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist (not imaged)

Attributed to Cesare da Cesto

Oil on panel

75 x 53cm

Château de Flers, Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France. Currently in Paris.

Budapest

Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist

Attributed here to Marco d’Oggiono

Oil and tempera on panel, possibly linden.

113 x 76.5cm

Museum of Fine Art, Budapest

The Tondo Group

Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist

Follower of Leonardo da Vinci (Niccolo Soggi?)

95.25cm diameter

Buscot Park, England

Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist (not imaged)

Follower of Leonardo da Vinci

Gallarati Scotti Collection, Milan

Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist (not imaged)

Follower of Leonardo da Vinci

Location unknown. Formerly in the Lockinge Collection, England

Historical, Stylistic and Iconographic Story

It is surprising that the Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist has been so little studied because it demonstrates a fascinating

phase in the development of the Madonna and Child composition during the Italian Renaissance of which Leonardo da Vinci was so

instrumental. How and when did the composition which forms the basis of the Moscow group originate? This is a more complicated question

than one might expect. Leonardo was known to linger over the subject of a painting during extended periods with often years passing before he

might return to or complete a picture. This was sometimes caused by problematic commissions but also by Leonardo’s apparent habit of

procrastination. It appears that the composition found in our painting resulted following a number of years and it explains the presence of

elements in the picture which can be found in other Leonardo works spanning several decades.

Figure 2. Vinci, Virgin and 3. Leonardo da Vinci, detail of Kneeling

Figure,

Child St. Joseph, Academia, Venice Figure Infants & Angels, Accademia, Venice.

Studies for one of Leonardo’s first known works, the Adoration of the Magi, an unfinished painting from 1481-2, just before Leonardo left

Florence for Milan, reveal the earliest origins of our composition. (figs. 2-4), The quickly sketched figures show Leonardo experimenting with

various poses. Although none of the Child drawings retained poses found in the Christ Child of the ‘core’ group, the Christ Child in the

Budapest picture does have its origins in these sketches in the reclining pose with one hand placed close to the mouth and the other sketch

showing the hand outstretched. These early sketches show how Leonardo approached his compositions, trying out various positions and

arrangements.

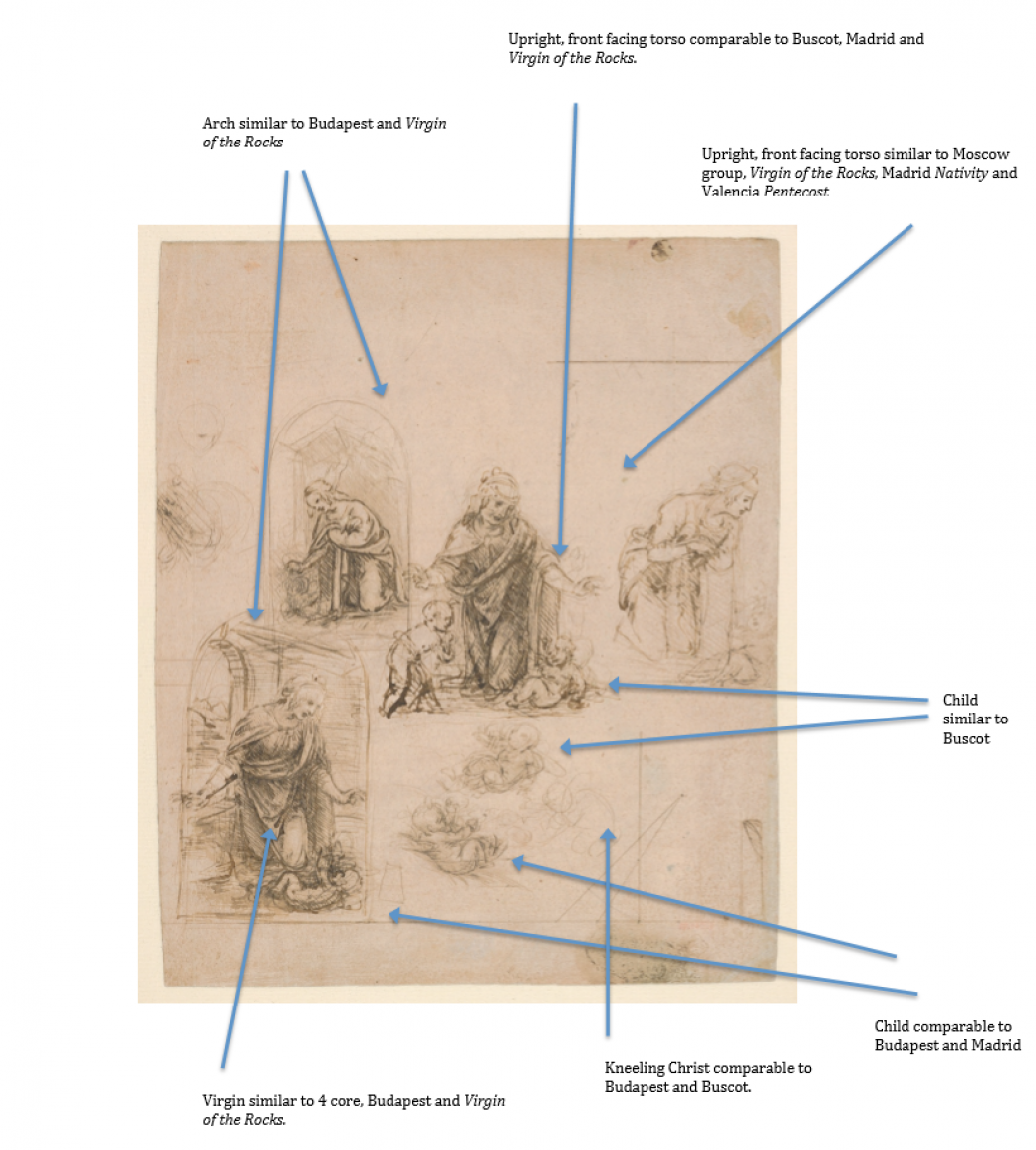

Probably the most significant sheet of Adoration studies for our group of paintings was created some years later and now to be found at the Metropolitan Museum, New York (fig 5). It is an important sheet for several reasons. Firstly, studies found there reveal Leonardo’s sophisticated

development of the subject. It demonstrates how the Moscow group is a significant link within this development. The sheet also depicts varying

figural positions which in some cases are found in our group of paintings as well as other examples but not in Leonardo’s own works. This is significant because it suggests that compositions around the subject of the Adoration were

worked up to such an advanced degree by Leonardo that they became part of the output of his studio, pupils and followers.

Figure 4. Vinci, Studies for adoration, Hamburg Figure 5. Designs of the adoration of the perspectival

projection of metropolitan Museum

Although sometimes dated to the early 1480s[1], the compositional advances as well as optical diagram found on the lower right date the sheet

more convincingly to the 1490s.[2] It also has affinities to a slightly earlier related sketch on blue prepared paper now at Windsor (fig 6). The

studies comprise a

varied sequence in the development of an adoration theme.

These compositions matured to those found in the two

Virgin of the Rocks as well as in various figures of the Moscow group. Indeed, this sheet can be viewed as a bridge between Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks, a troubled commission which ran for over twenty years beginning in 1483, and the Moscow group. It is therefore worth examining

these sketches in some detail.

In each of the studies, the Virgin is found kneeling in humility before the Christ Child, who lies on the ground. The kneeling Virgin apparently alludes to Saint Bridget’s

vision of the Virgin on her knees at the moment of Christ’s birth. The central composition was perhaps the first of the studies to be executed. It includes the St. John and is closest in composition to Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks. In this study, the Virgin faces the spectator with arms

embracing the space above the Christ and St. John, a gesture reminiscent of a Madonna della Misericordia. Leonardo then appears to have

created a more simplified composition less like the Virgin of the Rocks by removing the St. John, possibly in response to a reduced scale of the

composition. An arched frame is introduced perhaps to accommodate a known location for the work or to further elaborate the format. In the

lower left composition, the frame must have been added early on, as almost all of the drawing is within its boundaries. The S curve shape of the

Virgin, the arch of the stable and the diagonals formed by the roof all contribute to a dynamic composition of movement.

Martin Kemp’s suggestion that the optical diagram found on the sheet relates to Leonardo resolving the composition of a small-scale painting with the close range between the spectator and picture would apply to the purposes of our ‘core’ paintings which are smaller scale devotional

works.[3] Their role as more intimate objects for private devotion with the accompanying problems of close viewing was being studied by Leonardo as part of these studies.

The arrow-marked illustration of the MET sheet demonstrates the varying features and where they can be found in completed paintings, including the Moscow group, particularly the forward facing Virgin in the centre which also relates to the two Virgin of the Rocks.

[1] See Bambach, pp. 366-370.

[2] See Kemp in Bambach, pp 145-146. Kemp has pointed out that the optical diagram on the bottom right of the sheet is closely connected to

MS A in Paris dated to the 1490s. Disscussion with Kemp, November 2015.

[3] Ibid.

There are further observations to consider. Firstly, the Virgin’s pose in some cases echoes two paintings by the Spanish artists known to have worked with Leonardo in Florence during 1505, Fernando Llanos and Fernando Yanez de la Almedina (figs 78). The artists returned to Spain

around 1507 and soon after began a commission for Valencia Cathedral which included a painting of the Pentecost where the pose of the Virgin echoes the MET studies.[1] However, it even more closely resembles a flipped version of the 2011 discovery of underdrawing in the London

Virgin of the Rocks (fig 9) where the Virgin brings one hand to her chest.[2] A further Spanish painting of a Nativity with a Donor by Fernando Llanos includes not only the Virgin with outstretched arms found in the MET sheet, but also the reclining Child in a pose most closely

resembling the Child in Budapest. The Spanish artists have also been connected to another of Leonardo’s paintings, the Madonna of the Yarnwinder, of which two prime versions exist (fig 10). A number of versions of this painting survive in collections in Spain and it seems

evident Madrid. that the artists took the composition with them, either in cartoon form or with highly worked up drawings or possibly a painting

they had completed whilst in Florence. The Florence version of the ‘core’ group has been attributed to Fernando Yanez de la Almedina and this will be discussed later. Unfortunately little is known about either of the Spanish artists. However, their output demonstrates considerable knowledge of Leonardo’s studio up to around 1507, including compositions relating to our picture. [1] Interestingly, the architectural details in

the Nativity with a Donor are similar to those found in Durer’s woodcut of the Adoration of the Magi, c. 1501, Albertina, Vienna. See Benito, p. 123. [2] See Syson, pp. 64-67.

Figure 5. Fernando LLanos and Yanez de la Almedina, Pentecost

Figure 6. Fernando LLanos, Nativity with a donor, Private collection.

Figure 9. Tracing of underdrawing in Leonardo Virgin in Rocks, National Gallery, London

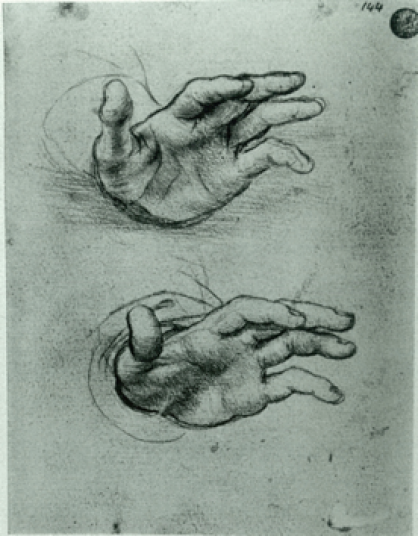

One drawing that relates our group of paintings with the Madonna of the Yarnwinder as well as the two Virgin of the Rocks and several Spanish paintings is a study for the right hand of the Virgin at the Accademia, Venice (fig 11).

The hand on the lower part of the sheet is very closely connected in particular to the left hand of the Virgin in the ‘core’ group while the

drawing above it is more like the one found in the Spanish Nativity with a Donor. The hand is a fine example of a single device created by

Leonardo spreading far and wide amongst his followers. Why would

such a seemingly small gesture become so popular? Perhaps the answer lies in the way in which Leonardo uses it. The gesture is one of

blessing. But it is also a sign of protection, in this case that of a mother with her child. The combination of religious blessing, maternal care and

the inevitable Passion creates a psychological impact which charges the story on an emotionally visceral level.

Figure 10. Leonardo DaVinci, Madonna and Yarnwinder, Private collection

Figure 11. Cesare da Cesto or Fernando Yanez de la Almedina, Study for a foreshortened left hand, Accademia, Venice

The

Budapest connection and Milan

Returning to the MET sheet, the arched border framing two of the studies and which also frames the two Virgin of the Rocks is also reflected in the Budapest painting (figs. 12-13.). Bearing in mind the other similar elements between the MET sheet and the Budapest picture, it is

reasonable to suggest that the sheet provides a kind of key to finding the place of the Budapest painting in our study. It appears to rest somewhere between the composition of the group in the Virgin of the Rocks and the Moscow composition so that its relevance to the Moscow group becomes quite important as a kind of precursor to it.

Figure 12. Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin of the Rocks

What else can we discover about the Budapest work? Like the Moscow painting, it is a considerably under researched painting. This is perhaps because until recently its poor condition has meant that it has been in storage at the Museum of Fine Art, Budapest for many years, unable to be

put on display or loaned to institutions. During 2006-7 the painting underwent an extensive conservation and restoration programme that

involved re-cradling the panel, cleaning and stabilising the paint surface and inpainting over large areas of paint loss, particularly in the head and chest of the Virgin. The panel is larger than the ‘core’ group, enough to have been commissioned for a church, but not as large as the Virgin of the Rocks.

Although the Budapest work is currently attributed to Salai, Leonardo’s long time pupil, it is more likely to have been executed by the Milanese artist Marco d’Oggiono or perhaps Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. Leonardo had arrived in Milan in the early 1480s and had been given the commission for the Virgin of the Rocks soon after. Two surviving notes by Leonardo, dated 1490 and 1491 strongly suggest that Marco d’Oggiono and Boltraffio were working in his studio, since Leonardo noted that both had been victims of the theft of a silverpoint by the precocious Salai. This would mean that the artists would have had direct access to projects and studies that Leonardo was undertaking. Other

artists known to have worked with Leonardo during his stay in Milan include Ambrogio de Predis and Giampetrino. Although Leonardo’s

influence on Milanese painters was enormous and lasted for decades after he left, the works produced by these artists were largely based on the emulation and repetition of Leonardo’s style rather than the use of it as a starting point for further advancing their own particular trademark.

With the exception of Boltraffio, it was perhaps also the case that many of these works convey only a superficial understanding of Leonardo.

Whether or not Marco d’Oggiono executed the Budapest picture, it is a strongly Milanese painting, unlike the more characteristically Florentine

style of the ‘core’ group. In this way the Budapest painting also represents a geographical as well as stylistic transition of the composition from Milan to Florence.

Figure 13. Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin

of the Rocks, National Gallery,

London

A probable link between Marco d’Oggiono and our ‘core’ group of paintings can be found in his Portrait of Francesco Maria Sforza (Il Duchetto) (fig. 14). Prominent in the portrait is a goldfinch with outstretched wings held firmly in the hand of the young boy. The goldfinch

was a common symbol of the Passion but was also kept as a pet in the Renaissance and perhaps it has this double meaning in this portrait. What is interesting is the similarity between this goldfinch and those found in varying positions particularly the open wings in the ‘core’ paintings.

Figure 14. Marco d’Oggiono, Portrait

of Francesco Maria Sforza (Il

Duchetto), Bristol Museum and Art

Gallery

How do Leonardo’s drawings such as the Adoration studies find their way into finished paintings of such variation? One reason, particularly in the case of the subject of the Adoration, was the length of time Leonardo worked on the commission for the Virgin of the Rocks. During a period of

more than twenty years the subject remained with the studio. This would have given plenty of opportunity for pupils and visiting artists to be

exposed to the ongoing work and to borrow from Leonardo. Given his fame, works with the Leonardo brand were in high demand and his

studio spawned many copyists clamouring to join the Leonardo bandwagon.

From Cat to Lamb

Alongside the Adoration studies, a second group of sketches comprising six drawings are significant to our study. They show Leonardo working on the composition for a Madonna and Child with a cat, several of which are found at the British museum. (figs 15-16). The subject is an unusual one because, aside from the legend that a cat had given birth at the same time as Christ was born, it has no links with the Passion of

Christ. Far more conventional animal symbols would include the lamb or goldfinch. Dated to around the same time as the early adoration sketches, these rapidly executed drawings show Leonardo brainstorming the interactions between the mother, child and cat, including several of the Christ in animated struggle with the animal.

Figure

15. Leonardo da Vinci, The

Virgin and Christ Child with a

cat, recto. British

Museum

These sheets vividly exemplify Leonardo’s pursuit of the best figural arrangement for his composition. Having worked over numerous options

on one side of the page, the scribbles become difficult to differentiate causing Leonardo to turn over the paper to continue the process on a clean sheet. This kind of creative process was one which Leonardo likened to a poet writing a poem and trying different words to find the best

solution:

Have you never reflected on the poets who in composing their verses are unrelenting in their pursuit if fine literature and think nothing of

erasing some of these verses in order to improve upon them? Therefore painter, decide broadly upon the position of limbs of your figures and attend first to the movements appropriate to the mental attitudes of the creatures in the narrative rather

than the beauty and quality of their limbs.

In the same way that a poet needed to experiment with words, the artist needed to explore the compositional possibilities for his figures. Leonardo referred to componimento inculto, an instinctive approach to making compositions that was imperative to the creative process:

You should understand that if such a rough composition turns out to be right for your intention, it will all the more satisfy in subsequently being adorned with the perfections suitable to all its parts.

Figure 16. Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Christ Child with a cat, verso British Museum

Figure 17. Attributed to Fernando Llanos or Fernando Yanez de la Almedina, Madonna and Child with a Lamb, Pinacoteca Nazionale di Brera, Milan

A painting in Brera and another Spanish connection

Although no painting survives with a Madonna and Child with a cat, intriguingly, a cat in the arms of the Christ Child has been found in the underdrawing of a painting of the Madonna and Child with a Lamb, now at the Brera, Milan. (figs 17-18). This painting is sometimes attributed

to the Spanish artists already introduced, Fernando Llanos and Fernando Yanez de la Almedina. The work is Florentine in style and a dating of

around 1505 or later is plausible. Whoever the artist was, it appears they had access to Lamb, Pinacoteca Nazionale di Leonardo’s decades

earlier Child and cat studies but Brera, Milan then ‘updated’ the composition to reflect the Master’s later project of the Virgin and Child with St

Anne (fig 19)Virgin and Child with St. Anne), which includes the Child with a Lamb.

There are also links between the Brera picture and the Moscow group. With the exception of the Budapest picture, all of the works share a

common background formula of a middle ground, complete with silhouetted tree on the right, leading to a body of water with buildings along one of its shores. There is a rocky hillside and in the distance mountains turned blue by aerial perspective. Like the Brera painting all of the

pictures from the imaging campaign include the columbine flower, symbol of Christ’s redemption. The red flower, possibly a poppy as a

reference to the Passion, found on the right side of the Brera picture is very like the flower to the left of the Madonna in Moscow.

Figure 18. Infrared reflectogram of the Madonna and Child with a Lamb, Milan

Figure 19. Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin

and Child with St. Anne,

Louvre, Paris.

Figure 20. Fernando Yanez de la Almedina, Madonna and Child with Infant St. John, National Gallery, Washington

A further painting, similar in size to the ‘core’ group and slightly larger than the Brera picture is another Madonna and Child with Infant St.

John, this time in

Washington and attributed to Fernando Yanez de la Almedina (fig. 20). Again, the progression from foreground to distant hills is familiar and in this case, more similar to the ‘core’ pictures with the rocky hillside found to the left of the composition. In this painting the Virgin’s raised hand

echoes once again the hand found in the ‘core’ and wider group as well as the Virgin of the Rocks and Madonna of the Yarnwinder. The figure

group is tightly formed like the Madonna of the

Yarnwinder and Brera painting. However, this time instead of embracing the Lamb, Christ, with legs in a similar position to a Getty sheet

(discussed below), reaches for St. John.

Christ Child and a Lamb

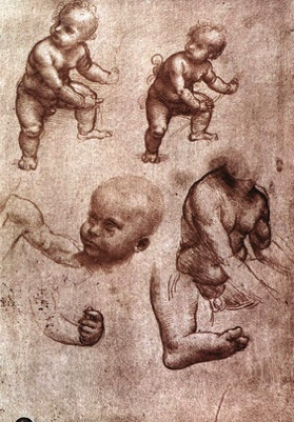

The transformation from cat to lamb establishes a link between the child and cat studies with a group of drawings of a lamb in the arms of a

young child. These studies, carried out some years later, can be dated to around 1500-1501, and are directly related to Leonardo’s painting of

the Virgin and Child with St Anne. The Child and Lamb motif, such a strong narrative element in that painting, is of course also found in the

Moscow work. How it found its way into the Moscow painting is worth exploring.

Figure

21. Leonardo da Vinci, Studies of an Infant holding

lamb, Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

There are several surviving drawings Leonardo da Vinci, devoted to the Child and lamb (figs 21-25) the pair in theVirgin and Child with St. Anne. Although none show the Child and Lamb in exactly the position found in the ‘core’ group, the pose is still the Getty (recto and verso) and

most recently discovered, with a lamb,Library, Windsor, Royal the back of the Virgin and Child with St. Anne panel. Unlike the Virgin and

Child with St. Anne picture, where the Child straddles the lamb, these examples show Christ seated in front of the lamb whilst embracing it, as in the Moscow picture. Although the lamb faces away from Christ in the drawing and the Christ’s legs are also positioned differently, the turned head of the Christ is very similar to the painting. The way in which the Lamb and Child are depicted looking away from each other in the ‘core’

group is worth noting. The outward turned gazes create an opposing tension in the painting. Although Christ has embraced the Passion, he is facing away from it as if reluctant. Leonardo’s interest in creating a psychological interplay between figures in his compositions will be discussed in more detail.

Figure 23. Leonardo da Vinci, Study of a child with a lamb, Royal Library, Windsor, 12539.

Figure 22. Detail of, Leonardo da Vinci, Study of seated nude and child with a lamb, Royal Library, Windsor, 12540.

Looking at the Getty double-sided sheet, one finds three sketches reworked in pen and brown ink on the recto. The position of the Child’s legs varies slightly between the studies as does the angle of his head. In a fourth and fifth sketch toward the upper centre and lower right of the sheet a similar sketch is faintly discernible in soft black chalk, and a further drawing can just be read at the lower centre. On the verso is another

sketch of the pair, this time larger in scale and animatedly reworked in black chalk. This sheet has often been associated with Leonardo’s lost

cartoon for the Virgin and Child with St. Anne, which was described by Fra Pietro da Novellara in his famous 3 April 1501 letter to Isabella

d’Este, one of the great patrons of the day. Supporting this hypothesis is the position of Christ playing with the Lamb, which is similar to that in the presumed painted copy by Andrea Brescianino after Leonardo’s lost cartoon (destroyed in World War II; formerly KaiserFriedrich Museum, Berlin). However, in the Brescianino version, the Child is standing with his knees bent rather than sitting as in the Getty, Windsor, Venice and Louvre drawings. Indeed, these drawings are far closer in composition to the Moscow work than to any other painting by Leonardo including

the Louvre Virgin and Child with St. Anne, where, of course, the Child is straddling the Lamb and also placed to the right of the picture.

Figure 24. Leonardo da Vinci, Studies for the Infant Jesus, Accademia, Venice.

Figure 25. Sketch of Christ Child on verso of Virgin and Child with St. Anne, Louvre, Paris

The connection between the Moscow painting and Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with St. Anne is an important one and can perhaps help us to more fully understand the iconographical development of the subject as well as to give the execution of the Moscow picture some kind of time frame. Leonardo’s first attempt at the subject of the Virgin and Child with St. Anne included a St. John the Baptist but not a Lamb. This is

exemplified in the London cartoon of the Virgin and Child With St. John the Baptist or the ‘Burlington House Cartoon’ from c.1500. Fra Pietro

da Novellara’s 3 April 1501 letter shows that Leonardo had produced another new cartoon, this time with a Lamb to replace the St. John. We do not know why this change was made. Perhaps it was to meet the wishes of a patron or perhaps Leonardo was refining his composition. Whatever the reason, the Christ and Lamb motif remained and it appears that the Moscow depiction of the pair developed from this 1501

representation or represents an earlier manifestation of the pair found in the Louvre painting. One thing is certain, the Child and Lamb motif

proved to be a very popular one. Not only were many copies of Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with St. Anne painting produced, but there were also many paintings showing only the Child and Lamb embracing.[1]

By the time Leonardo had returned to Florence from Milan, his reputation was well established. His technique for developing figural compositions was further enhanced by his deep interest in depicting the emotional narrative of a work. The simultaneous combination of these two distinctive developments cannot be underestimated for their influence on artists in Florence and beyond, including leading or soon to be leading artists such as Raphael and Michelangelo. If we return to the letters of Fra Pietro da Novellara it is evident that the psychological story which Leonardo wished to convey in his paintings was well understood by his contemporaries. When Fra Pietro wrote to Isabella d’Este, he described a visit he had paid to Leonardo’s studio. He had been directed by Isabella to find out why Leonardo was taking so long to complete a

work she had commissioned. In his 3 April 1501 letter, he described to Isabella a cartoon Leonardo was making for the Virgin and Child with

St. Anne. In the following passage Fra Pietro’s narrative of the composition involves a complex and symbolic interpretation:

[Leonardo] is portraying a Christ Child of about a year old who is almost slipping out of his mother’s arms to take hold of a lamb, which he

then appears to embrace. His mother, half rising from the lap of St. Anne, takes hold of the Child to separate him from the lamb (a sacrificial animal) signifying the passion. St. Anne, rising slightly from her seated position, appears to want to restrain her daughter from separating the

Child from the lamb. She is perhaps intended to represent the Church, which would not have the Passion of Christ impeded…[2]

This kind of portrayal of a devotional subject imbued with an emotional narrative was revolutionary. It was not only understood by Leonardo’s contemporaries as the letter and other accounts attest, but embraced by them. The Moscow painting, with its own Child and lamb also depicts a psychological story. Whist the Christ embraces the lamb and his destiny, perhaps reluctantly as the direction of his gaze implies, he is supported by St. John the Baptist and watched over by his mother. Her hovering hand protects the pair whilst allowing their embrace and therefore

Christ’s destiny. This is similar in psychological narrative to Leonardo’s Madonna of the Yarnwinder, the small devotional picture he was

painting around the same time and which also caught Fra Pietro’s eye. In a second letter to Isabella written eleven days after his previous

missive, he wrote:

The little picture he is doing is of a Madonna seated as if she were about to spin yarn. The Child has placed his foot on the basket of yarns and has grasped the yarnwinder and gazes attentively at the four spokes that are in the form of a cross. As if desirous of the cross he smiles and hold it firm, and is unwilling to yield it to his Mother who seems to want to take it away from him.[3]

As with the composition in the Moscow group, Leonardo injects an emotional narrative into the scene ingeniously depicting the conflict between maternal instinct and God’s will, between the role of a child and the role of the Christ Child. Fra Pietro’s interpretation of the symbolic and psychological narrative also demonstrates his understanding of Leonardo’s intention to create an emotional link between the spectator and

the figures in the story. No one had done this before. The composition found in the ‘core’ group succeeds in the same way and shows an

understanding of how to achieve this psychological intent.

Leonardo was notorious for not only not completing his paintings in a timely manner but also for not occasionally finishing the works at all. His Adoration of the Magi and St. Jerome are two examples of paintings that were never completed. The frustration of Leonardo’s contemporaries, patrons and friends alike, who perhaps wished the artist was more focussed on his individual works, is shared by historians today who

sometimes puzzle at the relatively low number of paintings attributed to the artist. There are a number of reasons for his rather modest and

sometimes incomplete output. Firstly, Leonardo was constantly taking up new interests or pursuing others that he would often obsess about, to

the detriment of his other obligations. We can turn again to Fra Pietro to see how distracted Leonardo was. In his 3 April 1501 letter he wrote,

From what I gather, the life Leonardo leads is haphazard and extremely unpredicatable, so that he only seems to live from day to day….He is hard at work on geometry and has no time for the brush…[4]

In his second letter to Isabella Fra Pietro wrote: ‘…[Leonardo’s] mathematical experiments have so greatly distracted him from painting that he

cannot bear the brush.’15 Both passages by Fra Pietro reveal Leonardo’s working practice, at least during this period, to be a rather

unregimented one. He would take up one pursuit only to be distracted by another. A further characteristic of Leonardo’s working practice was to constantly work over and over a subject in order to achieve a perfection which was often unattainable. His studies for a child and cat

demonstrate this. His well-known note to himself, ‘Tell me if anything was ever done?’ reflects a frustration he felt in pursuing the perfect

result. Perhaps this is one reason how a picture with a composition containing elements spanning decades in an artist’s career has come about.

The Imaging Campaign & Comparing the Paintings

(To be read in conjunction with report by Nicholas Eastaugh)

Between October 2015 and March 2016 visits were made to Oxford, Buscot Park, Florence, Budapest and Paris in order to study and capture infrared images of a series of paintings related to the Moscow Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist. Previous to this, in

August 2015, we were able to view the Moscow painting. It is extremely unusual to be given the opportunity to study a group of works in in

this way. The works were located in several countries, belonged to both private and public bodies and were often to be found in storage

facilities. However, we were fortunate to have most of our requests granted, with the exception of two X-ray requests for the Florence and Paris paintings which are still pending. We are nevertheless grateful to the institutions and owners for their generosity in allowing us access to their works. We are particularly thankful to the owner of the Moscow painting for giving us the opportunity to carry out our campaign.

The imaging was carried out with the use of two cameras:

- Canon 6D Mk1 modified for infrared imaging

20.2 megapixel Si sensor

Sensitive from 350-1100 nm (UV - NIR)

- VDS Vosskühler NIR-300PGE infrared camera

320x256 pixel InGaAs sensor

Sensitive from 900-1700 nm

Both systems were mounted on a Gigapan Epic Pro Tilt-Pan positioning head and using a Canon EF 400mm lens.

1000W Tungsten-halogen lamps with softboxes were employed for lighting when needed.

Note: The Moscow and Paris paintings were not imaged by Art Analysis and Research Ltd.

The ‘Core’ Group, Budapest and Buscot

What did we find? The results were in some ways quite surprising. We knew that the paintings would all be very close in composition and in

size and perhaps this led to an assumption that their execution would also be very close or at least very closely related. However, this appears not to be the case.

The very similar dimensions could suggest that the panels had been part of a supply held in a studio with copies duly being produced from that

stock. The panels were possibly made from different woods such as linden and poplar. However, identification of the wood cannot be confirmed at this time. None of the panels have been tested for wood species which would provide the best confirmation. The supports are all composed of a single board and vary slightly in the way they were assembled. The Moscow panel has a single horizontal cross-grain baton on the reverse while the Ashmolean panel has two cross horizontal batons, which appear to have been more recent replacement batons for earlier supports. The slightly differing methods of assembly could indicate that they were made by different panel makers, or perhaps because their assembly was tailored to reinforce each particular board. Usually the construction of a panel would have been made by a specialized artisan (legnaiolo) who could work independently of the studio or artist. In the case of the Paris painting, the verso of the panel was extremely rough and uneven. Panels of the size of the group were usually cut to a thickness of between 3.5 and 4.5cm and the ‘core’ panels share a similar thickness, with the Paris work slightly thicker and the Ashmolean slightly thinner. The Moscow and Florence supports were the most similar.

The Painted surface

It is not easy to make comparisons between pictures which are so different in their condition. The Oxford work appears to have been left largely

unfinished and this compromises attempts to make a judgement. Although the Paris work was also largely unfinished, this is chiefly in the

background so the central figures can be studied, albeit with some caution. On the other hand the Florence painting was completed and the

Moscow work appears to have reached completion or near completion.

There are striking similarities in not only the main figures of the Moscow, Florence and Paris paintings, but also in their secondary elements. For example, some of the flowers in the foreground can be found in one or more of the pictures. Also both the Florence and Paris paintings show the cross and cartouche with the same scattering of flowers to the right and roses by the Virgin’s right hand, while only the Moscow and

Florence pictures include the little daises by the Christ’s right leg. At the same time, both the Florence and Paris versions are close in their depiction of the Virgin’s brooch and dress trim, while the Moscow work shows somewhat different arrangement. Looking at the sleeves of the Virgin in the three versions once again one finds that the Florence and Paris pictures are more comparable.

Turning to the execution and treatment of the figures themselves, it is the Florence painting that appears to have resolved the modelling and

flesh tones more completely, particularly in the case of the Holy Children. This could be because of the present condition of the work in

comparison to the other ‘core’ picture. The brush strokes in the Florence work are barely discernible and the gradations of light are

convincingly executed. The handling of the flesh in the Moscow and Paris pictures is very different. The Paris work has a softer quality, perhaps

closer to the work of Cesare da Cesto to whom the painting has been attributed. The execution of the flesh in the Moscow work demonstrates a

great understanding of modelling and variations in light, but the extensive historical retouchings have somewhat compromised the outcome. However, it is evident that the artist who executed the main figures showed a high level of technical skill. Perhaps the only area where this is less the case is in the face of the Virgin. This appears to be the case with the Virgin in all of the versions where the modelling and specific features demonstrate less detail and subtlety.

Turning to the Buscot tondo, our visit to the painting enabled us to inspect a work that has been little studied. The available images were not good enough to make a clear judgement except to note the obvious relationship in some aspects of the composition. The artist who created this painting is unlikely to have been any of the artists who were involved in our ‘core’ group. The style and execution is more reminiscent of works by the pupil of Perugino Niccolo Soggi, and shows the influence of Florence-based Fra Bartolomeo, particularly in the saturated colours and

modelling of the figures. However, it is clear that the artist was familiar with the composition of the ‘core’ group and at some point had access to it either through drawings, cartoons or the paintings themselves. This is not an unlikely scenario as will be discussed later.

The Budapest painting on the other hand, appears to be a more significant painting to our ‘core’ group. As discussed, is can be viewed as a kind

of bridge between the Virgin of the Rocks compositions and that of our painting.

The conservation and restoration programme carried out during 2006-7 by Miklos Szentkiralyi, Bela Nagy and Disco Agnes, required a great deal of inpainting particularly in the areas of the Virgin’s head and chest. During our visit we were shown images of the work before restoration. It was interesting to note that the head of the Virgin showed underdrawing of a complex hair design, not unlike Leonardo’s Leda drawings at Windsor.

Infrared Reflectograms

Art Analysis and Research Ltd. captured infrared reflectograms for the Florence, Oxford, Buscot and Budapest and paintings. The Moscow painting was previously imaged using an Osiris camera and the Paris work was imaged by C2RMF (Centre for the Research and Restoration of Museums of France) to capture a range between 900 and 1700mm.

The resulting IRR images were varied in the information they gave us. Unfortunately, the Florence painting, the work which most closely resembles the Moscow picture, did not show very much underdrawing. This was the result with both the InGAs and Si sensors. Of course, this does not mean that no underdrawing is there rather that an undetectable medium might have been used. An X-ray, which could give us further information has been requested and agreed to, but we are still awaiting the results.

We were more fortunate with images from the Ashmolean and those provided to us by C2RMF for the Paris painting. Together with the IRR images from Moscow, they contributed to our investigation in two significant ways.

A study of the paintings under visible light has already suggested that the ‘core’ paintings were executed by more than one artist. The

underdrawings support this suggestion. This is particularly the case for the Paris painting which revealed the most extensive underdrawing. Very clear underdrawing can be seen in both Children and the lamb. The sketches are spirited and confident and include the designation of areas

to be shaded, such as the left leg of the Christ Child, and even very small areas such as Christ’s left big toe. The hands of the Virgin are also

clearly delineated, as are some quickly outlined areas in her drapery. It is possible that a comparison can be made between the Paris and

Moscow underdrawing. A similarity in the hatched shading strokes, more easily apparent in the Paris picture but also apparent in the Moscow

composition can be found. This is most evident in the Christ’s face, right arm and neck of the Lamb. It is therefore reasonable to suggest that the same artist might have taken part in the execution of the Moscow and Florence paintings.

A second way in which the IRR images have contributed to our investigation is how they reveal changes to the composition. Alexander Kossolapov has discussed this in his 2015 report. It is worth adding one or two thoughts. All of the ‘core’ pictures include the cross and cartouche in the underdrawing. The Ashmolean painting shows a just discernible cross but the cartouche is less apparent. Only the artist in the

Moscow painting chose to paint out the cross and cartouche. A probable reason for removing these devices was to create a less cluttered composition. The painting is not a large one after all. In the case of the Madonna of the Yarnwinder Leonardo had done a similar thing by first

including a basket in the composition and then choosing to remove it. Some copies of this composition include the basket and some don’t

suggesting that images of the work ‘leaked’ into other paintings before the final composition was completed. Did a similar thing happen to our painting? If so, it would suggest that the Moscow painting was the last work to be executed. On the other hand, it could also suggest that a

particular patron did not wish to have the cross and cartouche and requested that they be removed. Either way, the underdrawing does serve to further link the pictures in a way to suggest they were executed within a close circle of artists.

A further comparison between underdrawings considers the goldfinch held by St. John the Baptist. Under visible light it is just apparent that the

goldfinch in the Florence picture has opened wings while looking to the left, the Moscow goldfinch clearly faces to the left with its left wing outstretched while the Ashmolean and Paris versions are unreadable, the Paris version because of current conservation work. Looking at the infrared images reveals there to be changes in the position of bird’s wings and head position, perhaps suggesting that this detail was left to the

individual artists.

There were no obvious signs of the use of cartoons found in the underdrawings. However, as the compositions are so close in scale and size it is

suggested that some cartoon use was employed, perhaps using a medium not detectable with IR imaging. An exercise involving the overlapping

of the paintings showed only very small discrepancies between the works in the position of figures within the compositions. It could be that

cartoons for the individual figures existed and the compositions were copied in this way. A possible sign of the use of a whole cartoon for the composition does however exist for the Paris picture. The IRR shows straight lines along the inside border on the left, right and top of the

composition and these could have been made to mark the placement of a cartoon on the panel. Notable is the larger space between the line and edge along the left which corresponds more closely with how the composition is placed inside the three other ‘core’ panels.

Similar lines are can be found in the inside of the border of the Budapest IRR. As with the Paris painting, they are not visible on the surface of

the panel suggesting a use connected to the planning of the composition in the underdrawing stage, possibly for the placement of a cartoon as in the Paris work. There is very little discernible underdrawing in this work, aside from the Virgin’s head, as mentioned before, and drawing found in the drapery, particularly along the front of the Virgin’s chest, her sleeves and the drapery over her left arm, with an outline of her left arm also

showing. It seems that the drapery had once fallen to the ground beyond where it can be shown to her right. In this way, it is reminiscent of the drapery in the Paris version of the Virgin of the Rocks.

The painting at Buscot Park also revealed underdrawing in the drapery. Less underdrawing was found in the figures. However, areas of St. John the Baptist’s arms and face, the Christ Child’s face, and the Virgin’s hands and sleeves all show underdrawing and examples of pentimenti. The

background of this painting was also careful underdrawn, particularly the buildings and areas of landscape to right. The overall style of the

underdrawing executed by this artist does not resemble the underdrawing found in the ‘core’ group which reinforces the suggestion that a

different artist and probably studio was involved.

Why Replicate Paintings?

In order to understand why a painting of the Madonna and Child with Infant St. John the Baptist would be replicated it is important to

understand its context, that is, what was happening culturally and historically during the period it was made. During the late fifteenth and early

sixteenth centuries several major developments occurred which concern us. Firstly, the increasing wealth of Florence created an increased desire for material goods, including works of art. The huge demand for art, both private and public, in turn changed the way that paintings were being produced. At the same time, the Quattrocento style of painting led by Verrocchio, Domenico Ghirlandaio and others was followed by a new movement in painting initiated by the work of artists such as Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, Fra Bartolomeo and Andrea del Sarto.

These artists and their studios adapted to become in some cases prolific manufacturers of paintings, often repeating successful themes and

compositions or aspects of compositions through the use of cartoons and artists hired to execute copies or variants. The most successful studios were in effect operating two arms of a business. One was focussed on major commissions and a second arm was devoted to creating works

derived from the primary commissions. This approach made business as well as practical sense.

In taking on any issues of attribution regarding the Madonna and Child with Infant St. John the Baptist, it is important to understand the commercial and cultural contexts in which this painting appears to have been produced. Before we reach for the terms, ‘autograph painting’

and ‘workshop production’, we need to understand how these paintings were executed and the relationship between their production and the

market for which they were created. Understanding that these paintings were products of a business helps us to more deeply understand how and why they were produced. Master painters were in charge of a team of artists who were given specific and sometimes collaborative roles in

the production of paintings. The framework of each work was a combination of price and the desires of the patron, with the price dictating

which materials were used.[5]

Born from the practices of artists established during the last decade of the fifteenth century, such as Domenico Ghirlandaio, Alessandro

Botticelli, Filippino Lippi and Pietro Perugino, the studios of the early sixteenth century were in the business of producing everything from

large to small-scale commissions.

One of the most demanded subjects for paintings during the Renaissance was, of course the Madonna and Child. In Florence, the inclusion of that city’s patron saint, St. John, was a common addition. This group of figures would feature in countless devotional paintings of which the

Madonna and Child with Infant St. John the Baptist is one example. Artists would establish a particular style of painting these figures and

patrons would buy them for devotional and well as aspirational purposes.

Associations with particular artists were important to patrons. A combination of style, taste and political associations was embodied in these works. If a particular composition became popular, it would be reproduced as often as the demand required. From an artist’s point of view there

were clearly sound financial arguments in favour of making copies. Designs could be re-used and little time was lost in the planning. As the design was a familiar one, other members of the workshop could be employed in significant elements of the working process. The master was

on hand to offer guidance, and would be able to intervene to paint the finishing touches, or to lend a consistency to the overall style. Leonardo was known to have worked in such a way. Fra Pietro da Novellara helps us once more to illustrate this practice in Leonardo’s studio.

In his 3 April 1501 letter to Isabella d’Este, he recounts that, ‘two of his [Leonardo’s] apprentices are making copies and he puts his hand to one of them from time to time.’ The master might also be required to add an element to the composition that would personalise it to the patron. In this way a large number of works could be produced within a relatively short period of time and with a minimum amount of effort on the part of the master.

Other works executed by Leonardo in Florence during the period 1501-1506 that are known to have been copied by his assistants include the Mona Lisa, Leda, St. John the Baptist, and the Salvator Mundi.

Similar examples of close copying and reproduction of particular compositions emerge from many of the later fifteenth and early sixteenth

century workshops. These practices were also described by Vasari in this Lives of the Artists. One such example can be found in his life of

Giuliano Bugiardini (1475-1554). Bugiardini was apprenticed to Domenico

Ghirlandaio’s workshop and also worked with Fra Bartolomeo and Mariotto Albertinelli. This passage from Vasari describes how Bugiardini’s

talents as a copyist were utilised:

…other works of Giuliano’s [Bugiardini] having been seen by Mariotto Albertinelli, he recognised how careful Giuliano was in following the

designs that were put before him, without departing from them by a hair’s breath,and, since he was preparing in those days to abandon art, he gave him to finish a panel picture that Fra Bartolomeo di San Marco, his friend and companion, had formerly left only designed and shaded

with watercolours on the gesso of the panel, as was his custom. Giuliano, then setting his hand to this work, executed it with supreme diligence

and labour…[6]

In another passage from Vasari, we see how Bugiardini also collaborated with other artists. Vasari explains how he first worked in the Medici gardens where he came to know Michelangelo. Vasari goes on:

After Giuliano [Bugiardini] had studied design for some time in the above-mentioned garden, he worked, together with Buonarroti [Michelangelo] and Granacci [Francesco Granacci], under Domenico

Ghirlandaio, at the same time when he was painting the chapel in S. Maria Novella. Then, having made his growth and become a passing good

master, he betook himself to work in the company with Mariotto Albertinelli.[7]

Vasari’s passage is helpful in understanding an important element in the production of works of art. Artists were often involved in collaborative

work not just within their workshops, but outside them as well. A further reading of Vasari and other sources such as commissioning contracts,

is important in establishing the extent of the collaborative and developmental process in the art market. The artists were participating in a

culture of networking,

The artists were also learning from each other. One of Leonardo’s cartoons, executed in 1501, caused a sensation amongst not only the artists as

Vasari recounts. Although the cartoon he described appears to have been lost, another cartoon by Leonardo, with a similar subject, survives the National Gallery, London:

[Leonardo] did a cartoon showing Our Lady with St. Anne and the Infant Christ. This work not only won the astonished admiration of all the artists but when finished for two days it attracted to the room where it was exhibited a crowd of men and women, young and old, who

flocked there, as if they were attending a great festival, to gaze in amazement at the marvels he had created.[8]

An Assessment

Were the four ‘core’ paintings of the Madonna and Child with the Infant St.

John the Baptist part of a process of replication known to have existed in

Leonardo’s studio around 1501 when he was in Florence? Is one painting the ‘original’ or ‘prime’ version and the others copies made from it? Our ‘core’ paintings all share fundamental characteristics. They are almost exactly the same in size and scale suggesting the shared use of a

cartoon, parts of a cartoon, or some other replication technique. The central figures are extremely close in position and differ only in smaller details of those figures such as the Madonna’s brooch and the goldfinch. As with the two prime Madonna of the Yarnwinders, secondary

elements of the composition such as the flowers in the foreground and inclusion or not of the cross and cartouche differ. With the exception of

the Paris painting, probably because it was unfinished, all of the pictures also have very similar background.

Where the paintings diverge is in their condition and technical execution. Let us look first at their condition. Unfortunately, the Ashmolean picture is in very poor condition. It appears that the work was left unfinished. An attempt was probably made to complete it at a later date but

subsequent conservation interventions apparently severely damaged the surface to make much of it unreadable. The Paris painting has also

suffered. Like the Ashmolean work, this version was likely left unfinished. A later attempt to finish it appears to have caused damage resulting

in paint loss and an unstable surface. The paintings in Moscow and Florence are in comparably very good condition. Recent conservation work

on the Moscow picture (April 2015 by Larry Keith in London) has brought out subtle passages of sfumato not previously evident and cleaning

has given the palette a delightful cohesion.

Although the very varied condition of the works makes it somewhat difficult to fully assess, it is reasonable to say that they are technically

variable in their execution. Looking again at the example of the prime Madonna of the Yarnwinders, Leonardo’s hand is clearly seen in several key passages. The Lansdowne picture displays Leonardo’s characteristic curls of painted hair so comparable to the whorls of water he studied,

while the Buccleuch version includes the careful and accurate depiction of a crumbling and veined rock formation found in Leonardo’s

drawings and other paintings. At the same time, it is clear that other passages such as the background of the Buccleuch painting were carried

out by another artist not of Leonardo’s calibre.

Generally speaking, the level of execution in the Moscow and Florence paintings is substantially greater than the Oxford and Paris examples. Can Leonardo’s hand been discerned in the Moscow or Florence pictures?

Alexander Kossolapov has carefully laid out a proposal that suggests the Moscow picture was begun by Leonardo and completed by a pupil. In

his reading of the infrared reflectogram, he accurately describes the fragments of underdrawing that are evident and reasonably suggests that

other underdrawing might not be detectable with infrared imaging. Dr. Kossolapov also provides a convincing discussion regarding the inclusion and subsequent painting over of the cross and cartouche.

[1] See examples in Delieuvin, pp. 114-115 and 295-297.

[2] Villata, pp.134-5, no.150.

[3] Villata, pp. 134-5, no. 136.

[4] Ibid, no. 150.

Villata, p. 136, no. 136.

[5] The relationship between price and painting was a complex one in the Renaissance and more recent research has shown that the cost of

something had less to do with the cost of the material and more to do with the aspirations of the patron to express their own social virtues. See

O’Malley and Welch, 2007.

[6] Vasari, Life of Giuliano Bugiardini

[7] Ibid.

[8] Vasari, Life of Leonardo da Vinci.

Figure 26. X-ray radiograph detail of Child’s leg in Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, The Virgin and Child, National Gallery London

In his analysis of the X-ray radiograph, Dr. Kossolapov has made convincing comparisons between known Leonardo paintings and the Moscow

work, demonstrating how Leonardo’s use of lead white gives figures in the X-rays white highlights and sometimes a mask like quality to faces. He argues that the Moscow X-ray is comparable to X-rays of works of Leonardo. His examples include very reasonable comparisons between the head of the Virgin in the London Virgin of the Rocks and the head of the Virgin in the Moscow painting as well as between the Christ Child in the Munich Madonna of the Carnation and the Christ Child in Moscow. While these comparisons are certainly accurate, it is also true that Leonardo’s pupils and followers are known to have adopted the use of lead white for modelling developed by the master. This can be seen in, for example, Boltraffio’s Virgin and Child where an X-ray detail reveals apparent lead white modelling in the

Child’s leg. (fig 26). It is also found in the figures of the Budapest painting in the Moscow group.

Dr. Kossolapov proposes that the Moscow work was proposal that two hands were involved in the execution of the work. He goes on to suggest

that the work was begun by Leonardo and completed by a pupil. Although this is an entirely plausible and tempting suggestion, I suggest that

we would need further evidence to support it. We have still to find examples of Leonardo’s hand in particular. Can these examples be found? This might possible and I would wish to find such examples. However, it is equally important to bear in mind what we have found already and what we do know.

It could be that the Madonna and Child with the Infant St. John the Baptist is based on either a lost or unfinished painting by Leonardo. Such is the reasonable theory with five painted versions of the Leda, one showing a kneeling Leda, her children at her feet while the others depict her standing next to the swan with children also at her feet. Perhaps our painting is a parallel example of works created from a now lost original.

Drawings from around 1504 by Leonardo for both Leda versions exist at Windsor, Chatsworth and Rotterdam, but they are more advanced in

overall composition than any drawings relating to the Moscow group. And although there is no existing documentation contemporary to Leonardo regarding a Leda commission, a Leda by Leonardo was recorded at Fontainebleau in 1625 by Cassiano dal Pozzo, lending support to

the theory of a lost original. No documentation survives to record a commission for the Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist. The surviving painted copies of the Leda are all highly finished and are linked to close followers of Leonardo. This is less the case for the Moscow group, where two examples were left unfinished until a later date. Although the Florence version of the Moscow painting has been attributed to one of the Spanish pupils of Leonardo, none of the other works has an obvious Leonardo pupil contender. Perhaps this is because our group of paintings was executed one step away from Leonardo’s studio, possibly by a pupil of his unknown to us, or perhaps even a studio set up by the Spanish artists. It could be the case that although the composition for our painting firmly orginated with Leonardo and his studio, it was never

completed by him and instead migrated to the studio of one of his pupils. This could explain why there are relatively few versions of this

composition. All of this is of course supposition and, as mentioned earlier, there is the chance of finding further evidence, perhaps in technical examinations, to support Leonardo’s contribution.

If there is to be a case for Leonardo contributing to passages in the Moscow painting, it is reasonable to compare it to known Leonardo works. Let us look at some examples focussing on the main figures in the Moscow painting. One of the most captivating characteristics of Leonardo’s

work is his deep understanding of the underlying form and shape of the human figure. This understanding is combined with a highly

sophisticated and subtle application of very thin paint layers to build up a translucent quality to the shape and tone of the human form. When

comparing a detail of the head of St. Anne in Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with St. Anne at the Louvre with the head of the Madonna in the Moscow work differences in the execution of the two faces can be seen (figs 27-29). Other comparisons, shown in the accompanying figures, demonstrate further differences in the handling and execution of passages in Leonardo works and the Moscow painting (figs 30-39).

While Dr. Kossolapov’s proposals regarding Leonardo’s contribution to the Moscow work are entirely plausible I would wish there to be further

evidence to bolster the suggestion before agreeing entirely with his conclusions.

Conclusions

Although the research programme was not able to make definitive conclusions about a number of issues relating to the Moscow version of the

Madonna and Child with the Infant St.

John, it is the opinion of Martin Kemp and Thereza Wells that:

1) The four ‘core’ paintings are consistent with the system in Leonardo’s studio. They follow his use of innovatory inventions to produce

“Leonardobrand” small-scale devotional paintings in repetitions and variants.

2) The Moscow and Florence versions are of high quality and are produced by someone in or formerly in Leonardo’s studio.

3) The Moscow version appears narrowly preferable to the Florence version in quality.

4) There is at this stage no clear signs of Leonardo having been directly involved in the execution of the underdrawing or the final

painting in ways that match the execution of the two ‘prime’ Madonna of the Yarnwinders.

5) There probably was no Leonardo ‘original’ painting and the two best versions are what would have been regarded as ‘Leonardo’s’, that

is, works produced in the ‘Leonardo brand.’

Next Steps

There is no doubt that the Madonna and Child with Infant St. John the Baptist is an important painting in better understanding the work of Leonardo da Vinci. It’s composition reflects a phase in the artist’s development of compositions for the Virgin and Child with St. John the

Baptist which first began with his early Florentine Adoration of the Magi, continued with the Milanese period represented by the Virgin of the Rocks and found its place in the smaller devotional works such as the Madonna of the Yarnwinder. The figural composition and psychological

story are all Leonardo.

The Moscow group and its important contribution to Leonardo scholarship deserves to be better known. It is suggested that this could be achieved in the following ways:

1. A conference/workshop to focus on the process of replication in and beyond Leonardo’s studio with the Moscow group as a principal focus.

This would also serve to introduce the paintings in a scholarly way and provide an opportunity for other scholars to consider the paintings. A publication would be produced with contributions from Alexander Kossolapov, Martin Kemp, Thereza Wells and other Leonardo scholars.

2. An exhibition to involve as many of the ‘core’ group as possible, as well as supporting drawings by Leonardo da Vinci. This would fulfil the same purposes as the first suggestion.

Ideally the conference/workshop would be held together with the exhibition. It would be worth approaching a museum such as the Ashmolean. The 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death takes place in 2019 and this could be an opportunity for such an exhibition and conference.

3. Further technical research. It is unfortunate that the research programme did not have the opportunity to deeply investigate the Moscow

painting. A single study of the work without examination equipment in August 2015 was not ideal. An ideal scenario would be to have a fresh

programme of technical examination undertaken in a single campaign. It is suggested that this could be done in London at Art Analysis and

Research Ltd. Results could be published as part of the conference and exhibition.

4. Further academic research. There is still much that could be done in researching the Moscow painting in particular as well as the core group.

This could be in conjunction with the technical programme with a joint publication as a consideration.

Fig. 27. Detail of the head of the Virgin, Virgin and Child with St. Anne, Louvre, Paris.

Fig.

28. Detail of the head of the Madonna, Madonna and Child with St.

John the Baptist, Moscow.

Fig. 29. Detail of the head of the Madonna, Madonna and Child with

St. John the Baptist, Florence.

Fig. 30. Detail of brooch and neckline of the Virgin, Virgin of the

Rocks, National Gallery, London

Fig. 31. Detail of brooch and neckline of the Madonna, Madonna and

Child with St. John the Baptist, private collection,

Moscow.

Fig. 32. Detail of brooch and neckline of the Madonna, Madonna and

Child with St. John the Baptist, Florence.

Fig. 33. Detail of brooch and neckline of the Madonna, Madonna and

Child with St. John the Baptist, Paris.

Fig. 34. Detail of Christ and Lamb, Virgin and Child with St. Anne,

Louvre, Paris.

Fig

35. Detail of Christ Child and Lamb, Madonna and Child with St.

John the Baptist, private collection, Moscow.

Fig. 36. Detail of hand of the Virgin, Virgin of the Rocks, Louvre,

Paris.

Fig. 37. Detail of hand of the Virgin, Madonna and Child with St.

John the Baptist, private collection, Moscow.

Fig. 38. Detail of Christ, Virgin of the Rocks, Louvre,

Paris.

Fig. 39. Detail of Infant St. John, Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist, private collection, Moscow.

Bibliography

Bambach, Carmen, ed. Leonardo da Vinci. Master Draftsman, exhibition catalogue, New York, 2003.

Baldini, Nicoletta in G. Dalli Regoli, R. Nanni, and A. Natali, Leonardo e il mito di Leda: Modelli, memorie e metamorfosi di un’invenzione,

exhibition catalogue, Florence, 2001.

Benito, Fernando et al, Los Hernandos. Pintores Hispanos del Entorno de Leonardo, ehixbition catalogue, Valencia, 1998.

Bodmer, Heinrich, Leonardo. Klassiker de Kunst, Stuttgart, 1931.

Borenius, Tancred, “Madonna with the children at play”, The Burlington Magazine, LVI (March 1930), CCCXXIV.

Delieuvin, Vincent, ed., Saint Anne. Leonardo da Vinci’s Ultimate Masterpiece, exhibition catalogue, Paris, 2012.

Conti, Flavio in Palazzo Vecchio: committenza e collezionismo medicei, exhibition catalogue, Florence, 1980.

Giannattasio, P. in Ferrando Spagnuolo e altri maestri iberici nell’Italia di Leonardo e Michelangelo, exhibition catalogue, Florence, 1998.

Kamp, Martin and Walker, Margaret, Leonardo on Painting: Anthology of Writing by Leonardo da Vinci, 2001.

Kemp, Martin and Barone, Juliana, I disegni di Leonardo da Vinci e della sua cerchia. Collezione in Gran Bretagne, Florence, 2010.

Laurenza, Domenico, “Figino and the lost drawings of Leonardo’s comparative anatomy,” The Burlington Magazine 148 (2005), 173-179.

Möller, Emil, Die Madonna mit den spielenden Kindern aus der Werkstatt Leonardo, in “Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst”, LXII, 1928-1929.

Möller, Emil, Aggiunte e chiarimenti al tema “La Madonna coi Bambini che giuocana”, in “Raccolta vinciana”, XIII, 1926-1929 (1930).

Suida, Wilhelm, Leonardo da Vinci und seine Schule in Mailand. IV in “Monatshefte fur Kunstwissenschaft” 1920.

Suida, Wilhelm, Leonardo und sein Kreis, Munich 1929.

Syson, Luke and Keith, Larry, Leonardo da Vinci. Painter in the Court of Milan, London, 2011.

Villata, Edoardo, ed., Leonardo da Vinci: I documenti e le testimonianze contemporanee, Ente Raccolta Vinciana, Milan, 1999.

Wasserman, Jack, ‘A Rediscovered Cartoon by Leonardo da Vinci’, Burlington Magazine, 112, (1970), p. 201, n.26.

Thereza Wells

Head of Scientific Analysis at Universal

Leonardo

Comments made by Dr. Alexander Kossolapov

Head of the Scientific and Technical Examination Department

It is not very important or relevant to the main subject but I have certain doubts regarding your interpretation of a Cat which the Child holds in

his hands.

The cat, as far as I know, is famous for its killing a mouse who bored a hole in Noah’s Ark. Thus that creature took part in saving Mankind

and God himself put it since then under eternal human care and protection. So it is quite natural that The Savior holds another, “physical” savior

in his hands. Leonardo was quite familiar with the biblical Flood story - that found reflection in his corresponding drawings of later period;

I would not necessarily connect Madonna kneeling above the Child with St. Brigit vision. But this is not really important – you can interpret her

pose as you want.

You analyzed certain Leonardo’s drawings trying to connect those with “core” composition – the main subject of your study. Such approach

could have been workable for dating the Moscow composition provided that composition should be found in Leonardo's drawings. But there is

no such drawing known to us at this point! What is even worse, the drawings are not dated reliably. Thus, only approximate and quite broad time intervals for Leonardo’s developing core composition can be established. I return to this point below, but it seems to me of more

importance that those small drawings - sketches we know of, are too schematic to be considered as cartoons for Leonardo's studio/assistants to convert those into paintings. Those drawings rather reflect Leonardo’s ideas regarding his general concepts for future paintings he could have commissions for, while all versions of Adoration might exist before that (and not only in his mind but as normal full-size drawings or cartoons).

In other words, I would not accept (and I think I am not alone in that) that Leonardo communicated with his studio by means of small schematic sketches as the ones from the Met, from the Getty or from Royal collection. Those sketches were made for his personal use only, but not as

drawings to become working samples for his assistants.

By the way, the dating of the Met drawing to 90’s, seemingly basing on what you call “optical diagram” (in reality that diagram is perspective geometrical construction which shows dependence of linear size upon the distance from certain point placed into infinite distance) is not very

reliable. I would prefer conventional dating of the drawing to the beginning of 80’s. And this means that certain versions of Adoration could exist even before Leonardo's first sojourn in Milan.

In the “core” group, at least one painting, notably the Ashmolean version, could not be executed in Florence – it was executed in Lombardy, in Milan. And this is a fact as its panel wood, as I saw quite clearly when we visited Ashmolean together, is linden.Linden on panels we meet

normally in the North Italy, mostly to the North from Po River. To the best of my knowledge, no single linden panel of Florentine origin has ever been reported. From here if we follow your line of dating basing on the data (1501-1505), when the drawing of The Child holding

a Lamb was produced by Leonardo, one must say that Ashmolean version could not be created during the period between 1483 and

1499, i.e. during Leonardo's first sojourn in Milan. It should be dated by later period more or less synchronous with that drawing. Another point regarding the Ashmolean version is your statement that the painting was left unfinished. From what I saw, I would rather say that the painting is severely abraded. There is no technical proof, that I know of anyway, that it was left unfinished by its author.

From what we know from documents Hernando Los Llanos could not create his version before 1505 and he did that in Florence. The question

of what he used as a prototype for his work arises. I would not credit that author an ability to develop such composition by himself (and you

accept that the composition belongs in its main parts at the least to Leonardo). It seems to me that the Los Llanos Florentine version should be nothing else than a copy of another painting hold in the Leonardo's studio by 1505 - the absence of underdrawing on Los Llanos painting could be clear indication of his having copied not just something like the above mentioned sketch but another painting. The painting, not

cartoon or drawing. So, I am positive that certain painting – finished or unfinished modello which Los Llanos copied around 1505 existed in

Leonardo's studio. But which painting was that?

Our core group of currently known paintings leaves us just one possible original to copy – Moscow version. This is plausible by following

reasons:

- its quality is better than the Llanos version;

- in favor of its having been a sort of the modello speaks presence of two artistic hands on the painting. I have to repeat that firstly that

painting contained the faces and human figures only, everything else appeared there at the second stage of creation. This is not simply "plausible" as you put it, but this is a fact clearly seen on technical level of examination (please, refer to my report and to the radiography where you can clearly see the independent position of Madonna’ s head and breast – it certainly looks “ inserted" in her dress!!). I would repeat, this looks to me like original modello, dressed during some later stage of creation;

- in favor of this painting ( at modello stage) having belonged to Leonardo himself or its nearest circle speaks also usage of silver point for underdrawing. The silver point is also an established fact which by all means cannot permit dating the painting by later period. Silver point

practically came out of use after Leonardo's death, and it is worth mentioning that even during his life time there were quite a few artists, except his students, who were using that method of drawing. It is also worth mentioning here that the painting ground contains except gypsum also another material consisting of clay, silica etc. probably introduced to make the ground more rough-abrasive to ease silver point usage.

Talking about possible practice of multiple copying Leonardo's compositions in his studio and around it, you advanced an idea of special quest, sort of fashion, that has arisen in Italy for Leonardo' works. What is more, you tried to connect such fashion for paintings multiple

replication that would correspond to the rise of well-being of society people, who accumulated wealth that permitted them to order those numerous, famous name branded paintings. What time period and what region are you talking about?